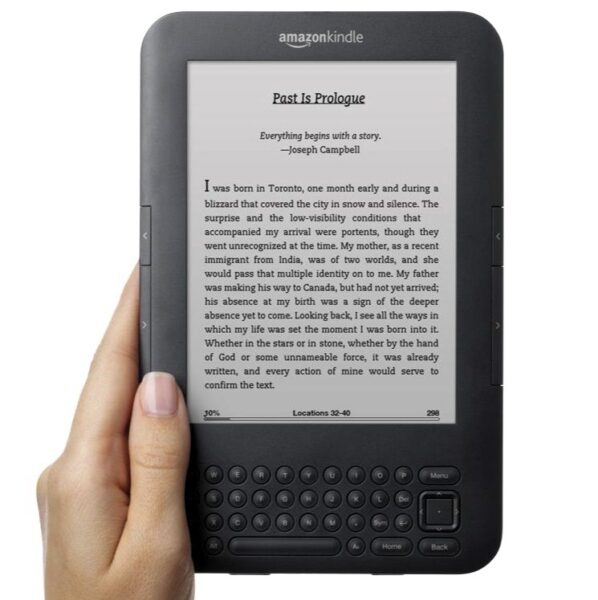

About 15 years ago, I bought my first device with an electronic paper (e-paper) display – the third-generation Kindle e-reader (also known as the Amazon Kindle Keyboard). I was immediately impressed by the readability of its 6-inch monochrome screen, especially when viewed under bright room lighting or even direct sunlight – a scenario that a liquid crystal display (LCD) of the era would struggle with. I was also impressed by how efficient this display device was, able to last several weeks on a single charge. Today, e-paper refers to several distinct display technologies that mimic the characteristics of a traditionally printed page while offering the advantages of a pixel-based digital device.

The exceptional energy efficiency of e-paper displays comes from their ability to update only when changes are needed – think of it as an organization of lazy pixels. Once an image finishes rendering on an e-paper display, little to no additional power is required to maintain its state. Compared to something like an LCD television, which constantly refreshes every pixel 50-60 times a second (or much more frequently) and uses a bright LED backlight array for illumination, the pixels of an e-paper display are reflective, utilizing ambient light sources to produce a visible image. For nighttime or darkroom viewing, manufacturers augment their e-paper displays with LEDs or electroluminescent materials.

Electronic Ink

One of the most popular types of e-paper display technologies involves particles suspended in a fluid-filled pixel that move when an electric field is applied, a process called electrophoresis. Nick Sheridon developed the first electrophoretic display (EPD) in the 1970s at Xerox PARC. It used half-black, half-white plastic microspheres, each side carrying an opposite electric charge (a dipole), suspended in oil that allowed them to rotate in response to the polarity of the applied voltage. This interaction caused each pixel in the prototype EDP to appear brighter or darker as the particles aligned with the pixel’s polarity. The oil’s viscosity helped maintain the spheres’ orientation even after the voltage ceased, significantly improving efficiency when displaying static images.

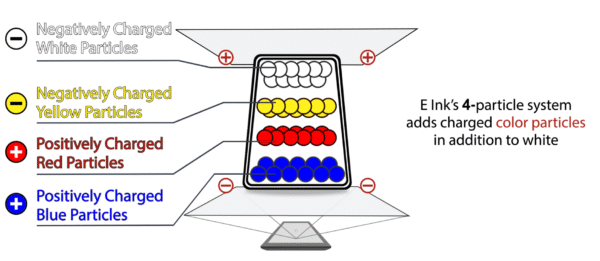

It’s impossible to talk about e-paper without mentioning E Ink. This company traces its origin to pioneering work on EPD technology at the MIT Media Lab in the 1990s. E Ink’s initial expertise included the development of e-paper “ink” technologies that featured encapsulated charged color particles suspended in a clear fluid that better resisted degradation, thereby extending the display’s usable lifespan. E Ink’s range of e-paper products now includes the use of a single particle color on up to four particle systems that offer an extensive color palette that can reproduce 10s of thousands of hues.

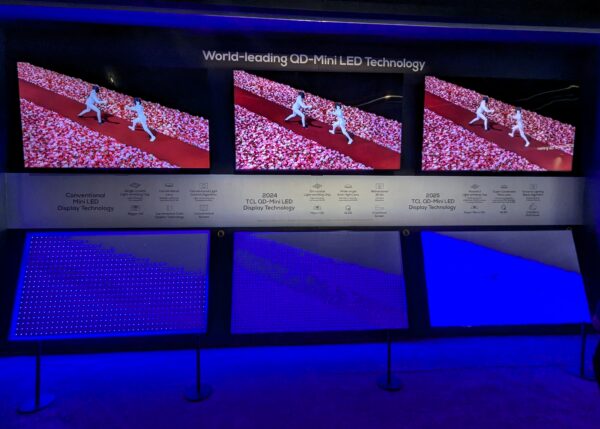

Acquisitions, mergers, and partnerships have resulted in E Ink’s technological and product domination in the EPD space. E Ink’s merger with a thin-film transistor (TFT) LCD manufacturer in 2008 helped scale production and drive technical innovations, just as the company’s e-paper displays were gaining significant recognition in products like the aforementioned Amazon Kindle – all Kindle devices manufactured to date have featured E Ink displays. In 2012, E Ink acquired a rival EPD company, SiPix, that specialized in a more structured system for containing encapsulated color particles that could offer improved image sharpness. The company’s latest color e-paper technology, Spectra 6, has enabled screen sizes up to 75 inches and is featured in products from a wide variety of display manufacturers, including BOE, LG, Samsung, Sharp, TCL, and many others.

Memory LCD

A couple of years after my first EPD product experience, I was fortunate to acquire the first edition of the Pebble smartwatch, which featured another e-paper technology still in use today, memory-in-pixel LCD (memory LCD). Memory LCD is similar in overall function to a traditional LCD used in laptops or TVs, except that each pixel features an embedded memory circuit that retains information about the pixel state, requiring very little power to maintain a static image. My Pebble watch’s monochrome memory LCD, manufactured by Sharp, offered excellent readability even in direct sunlight, and it incorporated an efficient three-LED edge-lit backlighting system for viewing in dim to dark environments.

Sharp’s memory LCD technology went on to power the follow-up Pebble Time smartwatch, introduced in 2015, that marked the wearable’s first color-capable display (64-color palette) and faster refresh rates. Today, I’m pretty impressed with the numerous features of a wearable like the Garmin FĒNIX 8 solar-charging smartwatch, which features Sharp’s latest iteration of memory-in-pixel color display technology.

Reflective LCD

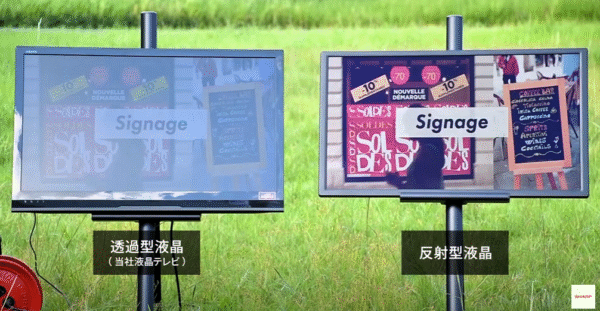

Another e-paper variant based on traditional LCD technology is reflective LCD. Reflective LCDs do away with the LED backlight array and replace it with a reflective layer that makes use of ambient light for illumination. Companies offering display panels based on reflective LCD technology include AU Optronics (AUO), Sharp, and Japan Display Inc. (JDI).

Compared to EPD displays, which can take several seconds to complete an update, reflective LCD designs are more responsive with a faster refresh rate of about 30 Hz, making them better able to display motion video compared to the relatively sluggish pixels of an EPD. However, that improved motion performance comes at the cost of increased power usage, and the LCD structure isn’t compatible with being incorporated into flexible films compared to other e-paper display types.

Electrochromic e-paper

Electrochromic-based e-paper displays take advantage of materials that can change color or opacity in response to an applied charge. The Canadian company Ynvisible has developed a water-based electrochromic ink that can be applied at scale using traditional printing methods and packaged into ready-to-integrate display modules. The company has optimized its e-paper designs for use in digital signage, indicators, and labels.

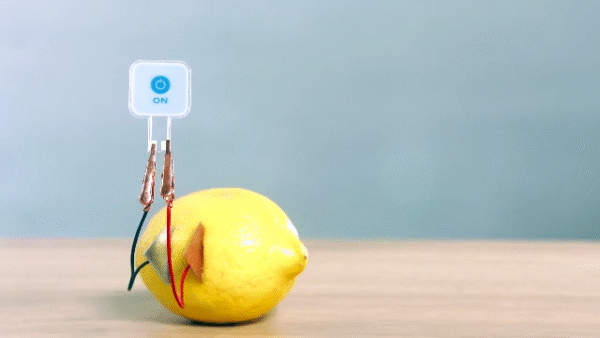

Ynvisible is quick to highlight the exceptional daylight readability and thermal stability of its products. When paired with protective UV films, Ynvisible’s e-paper displays are well-suited for outdoor applications, including below-freezing temperatures that can cause other e-paper technologies to take much longer to update or stop working altogether. Ynvisible’s electrochromic ink also boasts very low average power consumption, measured in a few microwatts per square centimeter of material needed to affect hundreds of segment-changing states. One of the efficiency demonstrations of Ynvisible e-paper indicators shows that a lemon battery can power it.

Efficient with Limitations

The diverse world of e-paper technologies is a testament to the ingenuity of scientists and engineers who are in search of effective display technologies optimized for low-power applications. The evolution of e-paper, particularly EPD-type displays, will likely never replace a television screen or signage application that calls for dazzlingly bright and saturated imagery that includes fluid video presentations, and that’s OK, as there are other mature display technologies better suited for that application.

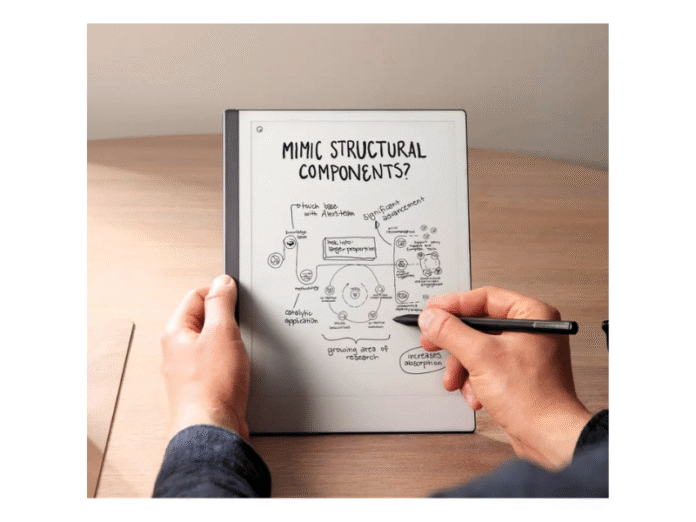

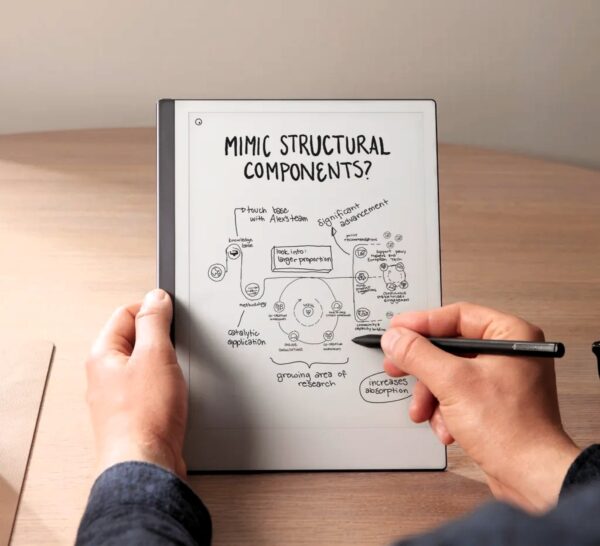

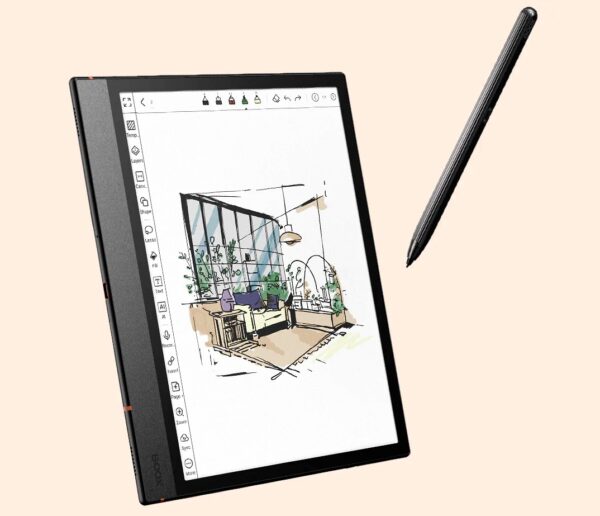

However, one new trick for the EPD e-paper devices we carry around with us is the enhancement of touch capabilities to include the use of electronic pens, with an experience closely approximating the feel of applying a pencil to paper. Companies like Boox, reMarkable, Supernote, and (of course) Amazon are producing compelling (and energy-efficient) e-notebook products with up to 300 PPI displays aimed at creativity, collaboration, and reading.

E-paper technology will always have a place for efficiently powered indicators and signage, and some of these display technologies will continue to prove themselves as the best option for wearables or devices we carry with us.

Robert is a technologist with over 20 years of experience testing and evaluating consumer electronics devices, primarily focusing on commercial and home theater equipment.

Robert's expertise as an audio-visual professional derives from testing and reviewing hundreds of related products, managing a successful AV test lab, and maintaining continuous education and certifications through organizations such as CEDIA, the Imaging Science Foundation (ISF), and THX.

More recently, Robert has specialized in analyzing audio and video display systems, offering comprehensive feedback, and implementing corrective measures per industry standards. He aims to deliver an experience that reflects the artists' intent and provides coworkers and the public with clear, insightful product information.